The idea of Good Omens is “Just William the Antichrist.” William was a character in the books of Richmal Crompton, a typical small English boy who was always getting into trouble but who possessed a kind of angelic innocence despite everything, and everything always turned out to be all right. For instance, when he pulled the lever in the train marked “In emergency stop train, penalty for improper use five pounds” (because he thought it if he pulled it just a little bit it would make the train slow down) it turned out that just at that moment a thug was menacing a woman in the next carriage and William was a hero. In Good Omens, Gaiman and Pratchett use a similar little boy, Adam Young, to do a comic take on Armageddon.

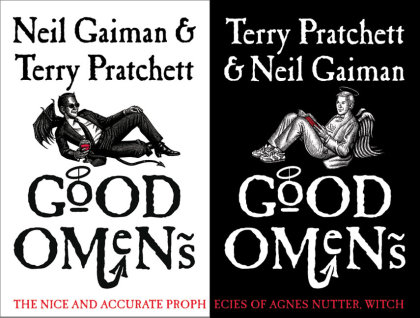

It’s an interestingly odd book, hilariously funny, very clever and not much like anything else. Heaven and Hell are trying to bring about Armageddon. Their agents on Earth, an angel called Aziraphale (who runs a second-hand bookshop) and a demon called Crowley (who drives a 1926 Bentley) who have had an Arrangement for quite a few centuries now by which they work together, realise that they quite like Earth and don’t want it to be destroyed. And this is the theme of the whole book, that it is humanity who are the best and the worst, Heaven and Hell don’t stack up.

“Listen.” said Crowley desperately. “How many musicians do you think your side have got, eh? First grade I mean.”

Aziraphale looked taken aback. “Well, I should think—”

“Two,” said Crowley. “Elgar and Liszt. That’s all. We’ve got the rest. Beethoven, Brahms, all the Bachs, Mozart, the lot. Can you imagine eternity with Elgar?”

Aziraphale shut his eyes. “All too easily,” he groaned.

“That’s it then,” said Crowley, with a gleam of triumph. He knew Aziraphale’s weak spot all right. “No more compact discs. No more Albert Hall. No more Proms. No more Glyndbourne. Just celestial harmonies all day long.”

“Ineffable,” Aziraphale murmured.

“Like eggs without salt, you said. Which reminds me. No salt. No eggs. No gravlax with dill sauce. No fascinating little restaurants where they know you. No Daily Telegraph crossword. No small antique shops. No interesting old editions. No—” Crowley scraped the bottom of the barrel of Aziraphale’s interests. “No Regency silver snuffboxes!”

Earth is stated to be better than the unseen Heaven, which is specifically said at one climactic moment to be indistinguishable from Hell. Very odd. It’s a relentlessly humanist message, as if Pratchett and Gaiman couldn’t quite summon up enough belief in the Christian mythos even to make fun of it. That I think is the flaw in the book. You can’t quite take it seriously, and not because it’s supposed to be funny (It is funny! It takes that seriously enough!) but because there’s a lack of conviction when it comes to the reality of the stakes.

There’s no problem with magic, or with the angelic and demonic nature of Aziraphale and Crowley. There’s no problem with the way all tapes in Crowley’s car turn into “Best of Queen” or the way they’ve been friends for centuries because they’re the only ones who stay around. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse are done wonderfully, and very memorably—Famine sitting around designing nouvelle cuisine and diet food and getting rich people to starve themselves, Pollution contaminating everything he sees, War the war correspondent always first on the scene, and Death, Pratchett’s Death who speaks in block capitals, busy working. (There’s a wonderful moment when he’s playing Trivial Pursuit and the date of Elvis’s death comes up and Death says “I NEVER TOUCHED HIM!”) There’s a woman called Anathema Device who’s the descendent of a witch called Agnes Nutter who left her a Nice and Accurate Book of Prophecy, which is always and specifically right, but written in a very obscure way. There’s a pair of inept Witchfinders, being funded by both Heaven and Hell. There’s Adam and his gang of eleven-year-old friends, just hanging out and being themselves. And there’s the world, the wonderful complex intricate world which is, in something like the opposite of Puddleglum’s wager, better than what’s been ineffably promised.

When I’m not reading Good Omens, I always remember the funny bits and the clever bits and the wonderful interactions between Crowley and Aziraphale. When I’m actually reading it, I’m always disconcerted by the way in which there’s a disconnect in the levels at which things are supposed to be real within the universe of the book.